The Golden Age of Replica Rolex Movements

Since the late 1990s, Rolex’s innovations in movement design, complications, and patents have flourished, often overshadowed by its iconic models and powerful brand presence. However, to fully appreciate the significance of this “golden era,” we must first look back and understand the groundwork that led to Rolex’s resurgence as a powerhouse of modern watchmaking.

The Rolex Landscape in the 1990s

The 1990s were a turning point for many industries, including watchmaking. As a child of the era, I became aware of the global watch scene around 1999. At the time, the cutting-edge watches featured complex calendars, rattrapantes, tourbillons, and chiming mechanisms – a territory dominated by prestigious brands like Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Vacheron Constantin. But in the midst of this, Rolex was as omnipresent as pop culture icons like boy bands and the tech boom.

In the 1990s, many Rolex models still relied on movement architectures from the 1980s, specifically the Caliber 3000 and 3135, and the brand’s offerings were relatively straightforward. You could choose between a GMT (Explorer 2) or a chronograph (Daytona). At this time, Rolex had not yet fully consolidated its movement manufacturing capabilities. For example, if you managed to secure a Cosmograph Daytona, it likely featured the Zenith-based El Primero Caliber 4030, assembled to Rolex’s specifications.

The Forgotten Complications of Rolex’s Past

Rolex’s history, however, is not one of simplicity. Looking beyond the 1990s, the brand had long been a champion of innovation. In the early 20th century, Rolex was at the forefront of technical advancements, such as pioneering water-resistant cases and automatic movements. The company’s watchmaking prowess during the 1930s through the 1950s is often overlooked, yet it was a time when Rolex produced watches with sophisticated complications.

The 1930s saw the creation of the Rolex Zerograph and Centregraphe, both featuring the in-house Caliber 10’5″ with a flyback function. The 4113 reference, with its split-seconds chronograph mechanism, represented the peak of replica Rolex’s ambition during that era, although it was produced in limited quantities. A decade later, in the 1950s, Rolex continued to push boundaries with the triple calendar and moon phase 8171 “Padellone” and its Oyster-cased counterpart, the 6062.

Rolex’s innovation continued into the 1950s with the introduction of the Dato-Compax “Jean-Claude Killy” triple calendar chronograph and the Tru-Beat “deadbeat” seconds of 1955. These groundbreaking models were indicative of Rolex’s commitment to fine watchmaking, sitting alongside the famous GMT-Master and Day-Date models that also debuted during this period.

The 1990s: A New Era of Innovation

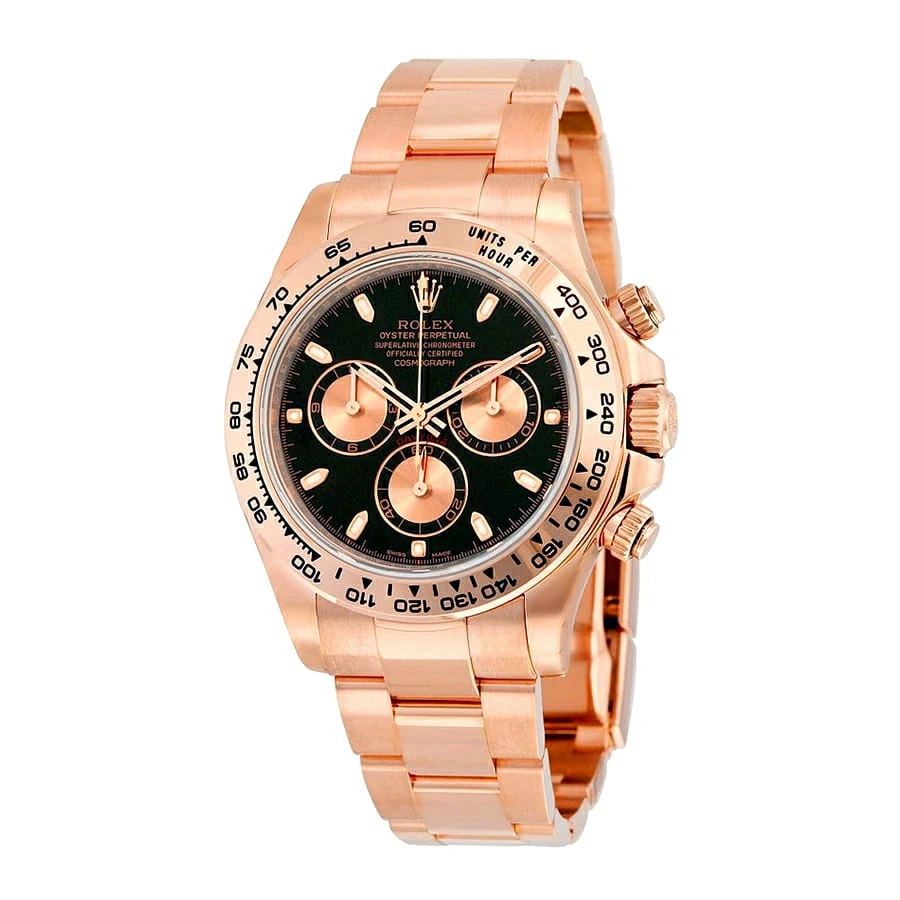

As the 1960s and 1970s saw Rolex refine existing models and invest in quartz technology, the company began to pivot once again during the 1990s. This shift was marked by U.S. patent number 5793708, filed in 1996, which introduced a significant innovation: a new chronograph mechanism with a vertical clutch. This development was a precursor to the now-famous Caliber 4130, the engine powering the modern Daytona.

The new Rolex chronograph was a massive leap forward. Compared to its predecessor, the El Primero-based Caliber 4030, the 4130 was a simpler, more robust design with fewer components, a full balance bridge, and the addition of hacking seconds. Its 72-hour power reserve placed it in elite company alongside other high-end movements from Blancpain, Patek Philippe, and IWC. With the release of the Daytona 1165xx at Basel 2000, Rolex signaled a new era in its movement manufacture, redefining the performance and reliability of its watches.

Rolex’s Full Ownership of Aegler: A Turning Point

In 2004, Rolex made a significant move by acquiring Aegler, the Swiss movement supplier that had been instrumental in Rolex’s watchmaking for nearly a century. This acquisition marked the beginning of Rolex’s full control over its movement production, a turning point that allowed the brand to take its technical expertise to new heights. The change would soon be reflected in the designs of its movements, and the brand’s transformation into a true manufacture was well underway.

Revolutionizing Movement Design

Rolex’s first major movement revolution after acquiring Aegler was the introduction of the 2005 Cellini Prince. This marked the brand’s first sapphire crystal case back in mass production, allowing collectors and enthusiasts a glimpse into the meticulously crafted movement within. The Prince was not only a tribute to Rolex’s history, but it also introduced a movement – the Caliber 7040 – designed for visibility and decoration, an ambitious departure from the brand’s previous philosophy.

The Cellini Prince was powered by the manual-wind Caliber 7040, a movement that took inspiration from replica Rolex’s vintage models but incorporated modern engineering for performance and aesthetics. The movement featured beautifully crafted bridges and a 70-hour power reserve, becoming only the second Rolex movement to achieve such autonomy after the Daytona. Each model was a certified chronometer, ensuring the same level of precision found in Rolex’s sports models.

The Future of Rolex Movements

The in-house developments seen in the fake Rolex Daytona and Cellini Prince were just the beginning of Rolex’s commitment to refining its movement technology. These early 21st-century innovations laid the foundation for even more groundbreaking advancements in the years to come. As Rolex continues to push the boundaries of watchmaking, we can expect its movements to remain at the forefront of the industry.